What was the Russian military story of 2019? Here are some possibilities:

- The July 1 fire aboard the AS-31 “Losharik” — a secret deep-diving nuclear-powered submarine — which cost the lives of fourteen Russian Navy officers, two of whom were already Heroes of the Russian Federation.

- The August 8 explosion near the Nenoksa test range in which seven Russian nuclear technicians died and others were severely irradiated, apparently while salvaging a nuclear-powered 9M730 Burevestnik (SSC-X-9 Skyfall) cruise missile that fell into Dvina Bay.

- The December 12 fire aboard aircraft carrier Admiral Kuznetsov caused by careless welding that killed two and injured 12 and could cost 95 billion rubles to repair. The ill-fated ship is already in an expensive overhaul and was damaged when it pulled away from its massive floating drydock in 2018.

But the real story — the tragedy — of the year is Ramil Shamsutdinov’s rampage. On October 25, the conscript killed eight fellow servicemen and wounded two more at his unit in Gornyy.

Ramil Shamsutdinov

His unit belongs to the MOD’s 12th GUMO — Russia’s nuclear weapons custodian. Gornyy is a “closed administrative-territorial entity” (ZATO) — a high-security area off-limits to all but personnel working in the facility.

He shot down officers, contractees, and conscripts at the end of his guard shift while they were unloading their weapons.

Only contractees are pulling guard duty there now, and, according to NVO, the unit will be disbanded and another will take its place.

NVO reported in early December that the MOD is extending its investigation into the case, and moving off its initial assertion that Shamsutdinov suffered a nervous breakdown because of “personal circumstances unconnected with his military service.”

Then the General Procuracy announced on December 24 that military prosecutors are investigating more than 40 units in Russia’s Transbaykal region following Shamsutdinov’s shooting spree. The procuracy spokesman said:

Simultaneously with overseeing observance of the law in the investigation of this crime, Main Military Procuracy, together with the RVSN’s military procuracy, in coordination with the task group established by the RF Minister of Defense for this crime, has organized joint investigative measures covering more than 40 military units.

He added that “making final conclusions about why Shamsutdinov committed the crime, and also about the conditions leading to it would be premature before the end of the investigation.”

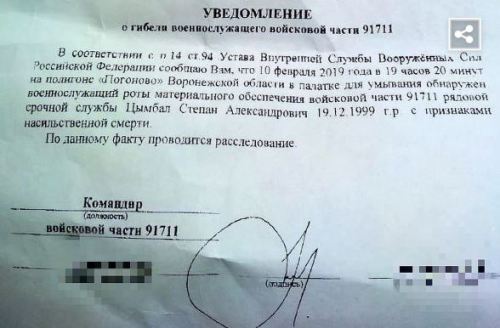

According to his lawyer, Shamsutdinov committed the crime because of criminal hazing by his commanders and fellow servicemen. He and several other soldiers in his unit were victims of violence and dedovshchina [the rule of the ‘grandfathers’ or senior soldiers, officially known as non-regulation relations between servicemen]. At least one of their reported tormentors is alive and has been formally charged.

This account of the Shamsutdinov case appeared in the MOD newspaper Krasnaya zvezda. So the Russian high command is pretty much on-board with these facts to date. It’s surprising the MOD would decide to look into another 40 units where similar grievous events could occur.

As Paul Goble observed the day after the murders at Gornyy, dedovshchina and violence in the ranks hasn’t receded into the past with the institution of one-year conscription making the difference between old and new draftees less pronounced or with the influx of “professional” contract soldiers.

He pointed to Ura.news which reported that the Transbaykal is an extremely remote backwater where bad officers often turn up. The same might be said of the entire Eastern MD. The distance to headquarters, poor communications and transportation, especially in winter, also weaken the chain of command. However, this happened in a unit with a critically serious mission.

An MOD source told Izvestiya in November the military will try to uncover problems in units by establishing a “sociological center” in each MD. Its personnel will assess the “moral-political situation” or MPS of units. Commanders reportedly will be accountable for a unit’s poor MPS up to and including dismissal.