Yes, Russia is making rockets now.

Vladimir Putin came to power on the eve of the 21st century promising (among other things) to remake Russian military power. But progress was slow. The economy struggled to emerge from the default and devaluation of 1998. A poor, unready army found itself mired for several years in the Second Chechen War.

Not until after an uneven military performance in the August 2008 five-day war with Georgia — and not until after the 2009 economic crisis, perhaps in 2012 or 2013 — did the funding necessary for significant improvements in combat readiness and larger procurement of weapons and equipment reach the Russian Armed Forces.

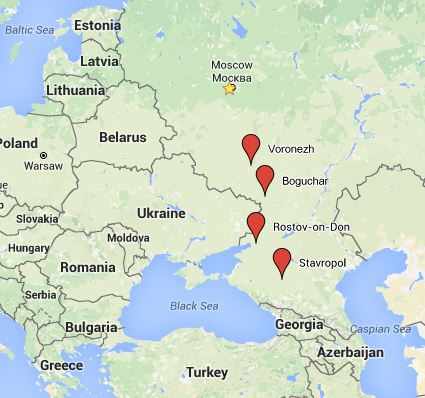

Then came war in Crimea and eastern Ukraine and Syria. Blowback from Syria could make Central Asia or the North Caucasus Russia’s next front. But questions about recent Kremlin bellicosity already bear close to home — on Russia’s domestic political and economic circumstances.

“But we make rockets”

“Can the army and navy replace everything else for citizens”

RS-24 Yars ICBMs on Parade (photo: AP / Ivan Sekretarev)

“Often it’s easier for people to accept growing financial hopelessness to the sound of bold military marches. Not for the first time in Russian history the army is beginning to replace the nation’s economy, life, general human values, and becoming the new old national idea and practically the only effective state institution.”

“Not everywhere in Russian industry are orders shrinking and demand falling. There is production that is very much in demand. In the ‘Tactical Missile Weapons’ corporation, for example, they’ve gone to three shifts of missile production for the Syrian front, a source in the defense-industrial complex has told the publication ‘Kommersant-Vlast.’ Against this backdrop, an article appeared in The Independent newspaper about how in Russia, after the events in Crimea and Syria, the army is again becoming the ‘departure point of Russian ideology’ — that very national idea for which they searched so long and unsuccessfully in post-Perestroika Russia and here now, finally, have found.”

“‘Russia has only two reliable allies — the army and navy.’ These famous words of Emperor Aleksandr III (who, incidentally, went down in history we would say now under the nickname Peacemaker) have once again in our history acquired a literal meaning. Other reliable allies of whom Russia was evidently sure over the last year-and-a-half or two years clearly no longer remain with us.”

“In a time of economic crisis, the temptation among Russian authorities to make the army one of the leading state institutions grows even greater. The remaining institutions are emasculated or work as badly as ever. In the end, to do this is sometimes simply useless: the impoverished voter will say — why are your institutions here, is my life improving? The expenditures are great, but the effect will be, probably, negative.”

“How much better the army is: there is discipline, and pay, and achievements, and a plan of development. The share of military expenditures in the budget is growing, but a cut in its absolute size has affected it to a lesser degree than civilian sectors like education and health care.”

“All hope is now on defense — as in ‘peace time’ we placed hope on oil and gas.”

“The army again is a lovely testing ground for demonstrating one more innovation — import substitution. Not all Russians can understand why it’s necessary to burn up high quality foreign goods. But hardly anyone would object that Russia didn’t buy any aircraft, tanks or missiles abroad. The president at a session of the Commission on Military-Technical Cooperation Issues announced that thanks to import substitution the country’s defense industrial enterprises are ‘becoming more independent of foreign component supplies.’”

“In general, we found by experience that we didn’t quite succeed in finding any other nation-binding idea over 25 years of not very consistent attempts to draw close to the Western world. The simple national idea ‘state for the sake of man’ didn’t take root, including, alas, because man somehow didn’t value it very much; attempts to raise free citizens and form a civic nation, bound by common human values, failed. There were neither citizens, nor values…”

“Being that there wasn’t demand for a free citizen not only above, but even below. It is precisely therefore that we don’t have normal trade unions, strong nongovernmental organizations, and independent civil initiatives. It’s not just the state that doesn’t need ‘all this.’ It’s society too.”

“Therefore one year before State Duma elections there isn’t even opposition in political parties to the openly military-oriented budget.”

“Distinct from this is that America which we love to accuse of aggressiveness, but in which military expenditures and their share in the budget are steadily falling in recent years. In fact, legislative control over the military budget is one of the main forms of civilian society’s control over the army in the USA. Though in America there were times when the military tried to decide both for society and for politicians. Considerable force and time was required to put the military under control, but the States succeeded in this.”

“In Russia the easiest and quickest means of unifying the nation turned out to be the bloodless victory in Crimea and the somewhat bloody events in the Donbass. The idea of abstract imperial power, and the image of ‘the country rising from its knees’ were substantiated, as the man in the street perceived it, and they were near and comprehensible to him. Like, we lead a miserable life ourselves (when was it otherwise?), but we are a ‘great power’ again.”

“Polite green people, capable quickly without noise and dust of ‘deciding questions,’ create in the multimillion-person army in front of the television an illusion of their own significance.”

“It’s not only the missile corporation that’s working ‘in three shifts’ now, but also the factory of national pride, based exclusively on military victories.”

“Firstly, we are proud of past victories, in which, besides the live heroes of that war, there is no one alive today who isn’t, in essence, a participant: St. George’s banners and inscriptions on foreign-made cars ‘To Berlin!,’ ‘Thanks granddad for Victory,’ ‘Descendant of a Victor’ flash at every step. Secondly, they actively urge us to pride in new military victories.”

“Meanwhile the war in distant Syria works for such military-patriotic PR even better than the war in Ukraine. And further from the borders, pictures of Russian aircraft bombing terrorists a world away inspire the people more than the sullen ‘militiamen’ of which the masses have had enough already.”

“What’s fashionable in war and militancy also enters official political discourse. Defense Minister Sergey Shoygu has firmly become the second most popular politician and most successful top-manager in the country. And the president not without some internal pride calls himself the ‘dove with iron wings,’ telling foreign guests directly at a Valday Club session that he was still in the Leningrad courtyard when he learned to ‘strike first’ if a fight is inevitable.”

“And it’s still necessary to remember: even a war far from the borders, if it’s protracted, requires not only military, but also great financial resources.”

“So if the economic collapse in Russia continues, pride in the army still cannot fully make up for people the absence of conditions for a normal life. But for now — in a situation where the authorities live by tactics and not by strategy, — the army and military mobilization of the nation really look like a national idea, and a panacea for the crisis, and a means of supporting a high rating.”

“Polite green people are already capable of becoming not simply a symbol of the Crimean operation, but a symbol of an entire epoch. But they usually don’t solve all the accumulated social, economic, and human problems of a large country.”